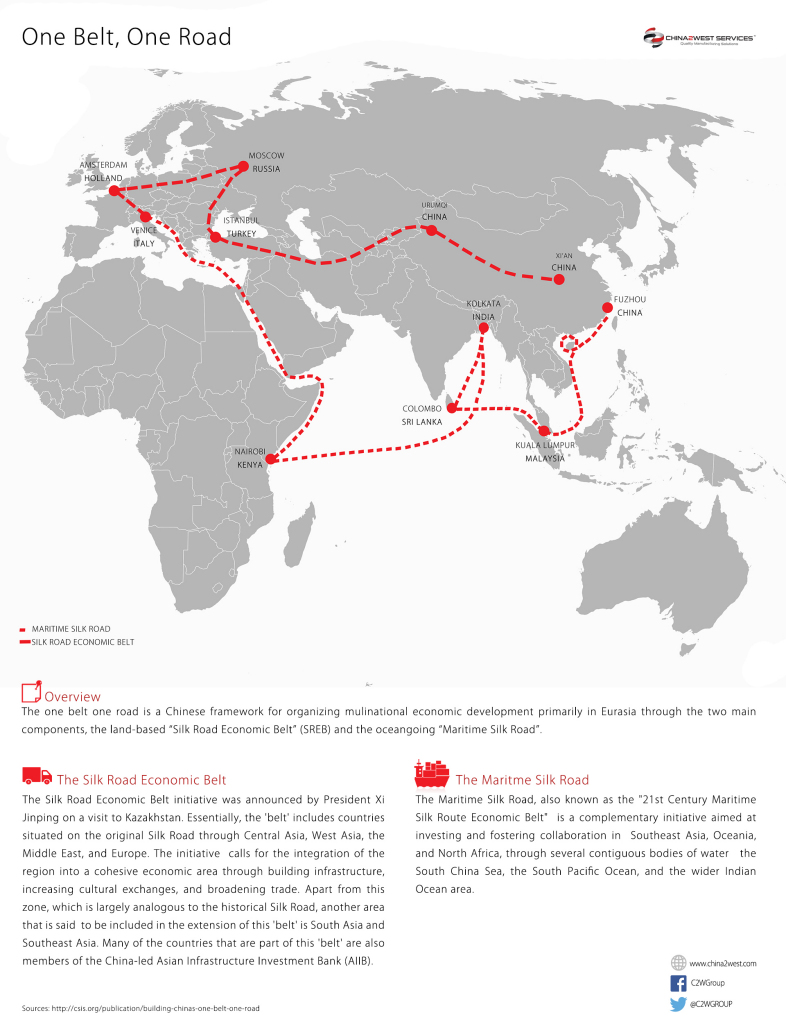

On March 28, China’s top economic planning agency, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), released a new action plan outlining key details of Beijing’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative. Chinese president Xi Jinping has made the program a centerpiece of both his foreign policy and domestic economic strategy. Initially billed as a network of regional infrastructure projects, this latest release indicates that the scope of the “Belt and Road” initiative has continued to expand and will now include promotion of enhanced policy coordination across the Asian continent, financial integration, trade liberalization, and people-to-people connectivity. China’s efforts to implement this initiative will likely have an important effect on the region’s economic architecture—patterns of regional trade, investment, infrastructure development—and in turn have strategic implications for China, the United States, and other major powers.

What is Beijing trying to achieve with this initiative?

The Chinese government has two aims with the implementation of the One Belt, One Road. Firstly it is searching to have a positive impact on its slowing economy and secondly to improve its foreign policy. The Chinese leadership is struggling to manage a difficult transition to a “new normal” of slower and more sustainable economic growth. The infrastructure projects proposed as part of the Belt and Road—many of which would run through some of China’s poorest and least developed regions—could provide stimulus to help cushion the effects of this deepening slowdown. Beijing is also hoping that, by improving connectivity between its underdeveloped southern and western provinces, its richer coast, and the countries along its periphery, the Belt and Road will improve China’s internal economic integration and competitiveness and spur more regionally balanced growth. Moreover, the construction is intended to help make use of China’s enormous industrial overcapacity and ease the entry of Chinese goods into regional markets. At a time when many large state-owned enterprises are struggling to stay afloat and banks are stuck in a cycle of rolling over ever-growing and progressively less viable loan portfolios, the projects that make up the Belt and Road could provide vital life support and serve as a useful patronage tool for compensating vested interests threatened by efforts to implement market-oriented reforms.

On the foreign policy front, the Belt and Road reflects many of the priorities Xi Jinping identified at a major Chinese Communist Party gathering on foreign affairs held last November. These included a heightened focus on improving diplomacy with neighboring states and more strategic use of economics as part of China’s overall diplomatic toolkit. Against the backdrop of a regional “infrastructure gap” estimated in the trillions of dollars, the initiative highlights China’s enormous and growing resources and will provide a major financial carrot to incentivize governments in Asia to pursue greater cooperation with Beijing. Over the medium to long term, successful implementation of the initiative could help deepen regional economic integration, boost cross-border trade and financial flows between Eurasian countries and the outside world, and further entrench Sino-centric patterns of trade, investment, and infrastructure. This would strengthen China’s importance as an economic partner for its neighbors and, potentially, enhance Beijing’s diplomatic leverage in the region. Increased investment in energy and mineral resources, particularly in Central Asia, could also help reduce China’s reliance on commodities imported from overseas, including oil transiting the Strait of Malacca.

Does this initiative involve a free trade area or the creation of another kind of international institution?

No, this is clearly not a regional free trade area, and it involves no binding state-to-state agreements. Instead, it is at its heart a pledge by China to use its economic resources and diplomatic skill to promote infrastructure investment and economic development that more closely links China to the rest of Asia and onward to Europe. In this regard, it reflects China’s preference to avoid if possible formal treaties with measurable compliance requirements in favor of less formal arrangements that give it flexibility and allow it to maximize its economic and political skills.

What are the potential benefits to Asia?

The “One Belt, One Road” has been referred to as China’s version of the Marshall Plan, a comparison Beijing has sought to downplay as being freighted with geopolitical undertones that it claims are absent in its initiative. Motivations aside, the initiative is a powerful illustration of China’s growing capacity and economic clout—and the Xi administration’s intent to deploy them abroad. Properly implemented, the projects that comprise the Belt and Road could help enhance regional economic growth, development, and integration. According to the Asian Development Bank, there is an annual “gap” between the supply and demand for infrastructure spending in Asia on the order of $800 billion. Given that infrastructure is at the heart of the Belt and Road, there is room for the initiative to play a constructive role in regional economic architecture. In addition, if this leads to more sustainable and inclusive growth, it could help strengthen the political institutions in the region and reduce the incentives and opportunities for terrorist movements.

What are the potential risks?

Implementing the Belt and Road will entail significant risks and challenges for China and its neighbors. Beijing’s past difficulties investing in infrastructure abroad, especially through bilateral arrangements, suggest that many of the proposed projects could well end up as little more than a series of expensive boondoggles. Given Chinese construction companies’ poor track record operating in foreign countries (including frequent mistreatment of local workers), a major increase in the scale of their external activities increases the risk of damaging political blowback that could harm Beijing’s image or lead to instability in host countries—particularly if the efforts do not generate lasting benefits for local economies. Enhanced regional connectivity might also increase the likelihood of the consequences of poor conduct abroad finding their way back to China.

Another risk is that many countries in Asia and abroad (including the United States) are concerned about the geopolitical impact of the Belt and Road. Although Beijing has sought to allay these concerns in its latest plan, stressing the “win-win” potential of the initiative, its efforts will have important foreign policy implications for a number of key regional players, including Japan, India, and Russia. Moscow is particularly concerned about the initiative translating into increased Chinese influence in Central Asia, an area it has long viewed as within its sphere of influence and where Sino-Russia competition has been noticeably intensifying of late. Meanwhile, India has been especially alarmed by Chinese investments in Sri Lanka, which New Delhi likewise views as part of its backyard.

Hence, there is a clear risk that Beijing’s efforts—well-intentioned or not—will heighten geopolitical tensions in an already tense region. There are also direct security implications of the project. The Maritime Silk Road in particular will likely expand China’s capacity to project its growing naval power abroad, while increased Chinese involvement in building regional information technology infrastructure could create new channels for Beijing to exert its influence in the region.

Alternatively, there is a substantial chance that these lofty plans will not come to fruition. China’s development strategy of “build it and they will come” has already run into difficulty at home. Should the same thing happen abroad, it could generate not only political backlash against China, but borrowers’ failure to pay back their loans, or businesses’ inability to recoup their investments could end up placing additional stress on the Chinese economy rather helping to marginally ease a deepening slowdown.